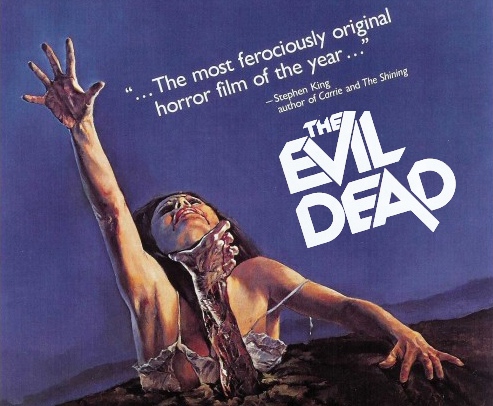

Several Hot Takes About The Evil Dead

1. Evil Dead is

scary. Like, actually scary.

It’s all but

scientifically proven; horror movies get me worst (best?) when I think they

can’t hurt me. An infamously scary film is watched with lights on, volume down,

emotional barrier and snarky attitude up, and, most fatally of all,

expectations high. Nothing is ever as scary as it is in my wildest imagination,

and the movie is doomed to be “not as scary as I expected.”

Alas, I’d

first seen Evil Dead 2,

double-featured with the tonally similar Reanimator

on the very night I turned in my application to Yale. ED2 is a combination sequel and parody, Sam Raimi’s more raucous

riff on the original film, too slapstick to be scary. But, horror completist

that I am, I knew I had to watch the infamous original. Since its sequel didn’t

scare me, the first one didn’t stand a chance.

Naturally, I

decided to watch Evil Dead after

returning from a jaunt in the woods. My family lives in Appalachian Virginia,

not all that far afield from Tennessee where the movie was shot. Proximity

maximizes horror’s effect – Halloween is

scarier in the suburbs, and I recently had the spine-tingling experience of

watching Black Swan in the Upper West

Side, not far from the Lincoln Center. But location counts for even more than

usual with ED, because its number one

monster is the woods itself.

While ED2 moves with breakneck speed through a

modified recap of the first film to get to the demon antics we know and love, ED takes it time. Our five seriously

screwed students settle in at their cabin; we have a little time to get to know

them and, more importantly, the woods around them. POV shots zoom through the

trees, accompanied by a truly disturbing sound of monstrous wind. Even before

the trees come to life, we get it. The woods are alive with the sound of evil.

It’s fucking

effective. It probably would have been effective in my girlfriend’s apartment in

New York, or in my dorm in New Haven, but it was about twenty times more

effective at my parents’ house, so surrounded by trees that it’s invisible from

Google Earth, having paid my own less hazardous visit to a cabin in the woods

just hours before.

Staying up late

and looking out the window at the darkness of the front yard, as the street

lamp on the curb flashed on and off, and listening to the sound of the wind

through the trees, I knew I was doomed to nightmares.

2. Evil Dead is

a psychological thriller.

The Evil Dead franchise is famous for two

things; mountains of goopy gore that got the movie caught up in obscenity

trials in the UK no matter how many ridiculous colors it was, and Bruce

Campbell’s manic, macho turn as the iconic Ash. It is not known for narrative

subtlety, nuance, or restraint. But if actually thought about, ED has one of the nastiest premises of

any horror franchise. And as the version of the story that eases most slowly

into the horror, ED gives an audience

the most time to ponder that.

Evil Dead is a movie where

the monster is all around. It is the forest and the trees that surround the

cabin; it is the cabin itself which can gush blood, blast music, and cackle at

a moment’s notice. It is the force of nature that can blow out the bridge that

is the only escape. Unlike in most horror, particularly the slasher of the era,

it is not embodied in one body or one form. Michael Meyers may be unstoppable,

but he’s confined to his shape. The titular evil of ED is shapeless.

Worse is what

the evil can do. ED is a movie in

which our hero’s friends are possessed one by one, with little warning. It’s

unclear what happens to them when they become Deadites; are they still there,

inside their newly monstrous head, staring out from behind the dinner-plate

contact lenses. Or are they just gone? Either thought is chilling. Future

iterations of the story raise the possibility of being brought back from

possession, but in the original film, this is only to further mock Ash, as his

girlfriend Linda slips in and out of demon-face to taunt him and exacerbate his

grief and indecision. Campbell’s Ash in the first film is different from the Ash

he will play time and time again in future installments. He’s not an action

hero; he’s sensitive. He mourns. The nature of possession forces Ash to

dismember the Deadites. In ED, Ash

raises the chainsaw over his possessed lover’s incapacitated body but can’t

bring himself to cut her to bits. He buries her instead. At the film’s

conclusion, his use of the necklace he gave her to burn the Necronomicon

reminds us of what he’s lost. And, without knowledge of the sequels, it seems

that Ash himself is possessed in the final shot as the POV camera charges

towards him. His suffering has been for nothing.

Without the

camp and slapstick and fun that the films, the original included, layered on,

that’s a bleak story. One can imagine Lovecraft whipping up something that digs

into the fatalistic, cosmic tragedy of it all. The first movie has its moments

of levity but is imbued with the darker implications of its goings on, especially

since the Deadites aren’t newcomers to the cabin, as in most of the second

film, but Ash’s loved ones. It’s no wonder future movies (not to mention the

fabulous musical) took such a turn for the campy; otherwise, it’s a bleak,

bleak tale.

3. Evil Dead is

an inverted slasher film.

In

many ways, ED is a typical horror

flick of its era: made dirt cheap and shot in a single location by a novice

director and crew, with healthy helpings of gore and a storyline which picks

its small cast off one by one. It’s story elements of a cabin with a spooky

basement, an evil forest, and five college students who meet a nasty end there,

would become rote horror tropes, cribbed/parodied most directly by Cabin in the Woods.

But

the typical slasher flick follows a familiar formula; bad guy stabs and slices victims.

The hero may turn the tables on the baddie and enact sometimes brutal violence

in return (see everything from Last House

on the Left to Get Out to every

Final Girl ever), but in Evil Dead,

the dismemberment duties fall to the hero from jump. Monstrous bodies are mutilated

with violence we should hypothetically root for.

Well,

kind of. The Deadites and the demon force violate and possess, disfiguring human

bodies as they do so. Luckless Cheryl is, infamously, grotesquely, raped by a

tree. The possessed Cheryl stabs Linda with a pencil. But this is small

potatoes compared to the gruesome violence enacted against the Deadites –

Shelly’s dismemberment, Linda’s decapitation, and the endless decomposition of

Cheryl and Scott after Ash burns the cursed book.

ED

functions like a violent zombie action movie within the close physical confines

of early Romero. The possession and absolute evil in the woods revokes societal

norms like not chopping up your friends. We sympathize with Ash’s turn to

brutality; the movie gives him no other choice. But we also understand why,

when newcomers arrive to the cabin in the second film, blood-splattered Ash

looks like a murderer and a madman. The movie’s conceit allows the audience to

sympathize with a hero committing the kind of chainsaw-and-ax violence that

usually only slasher baddies and the most badass of Final Girls get to commit,

without being precipitated by parallel violence towards him and his

compatriots.

Perhaps

relatedly, Ash is the rare example of a Final Boy. Why on earth does he hold

out against possession for almost the entire first film, and return from it in

the second? Why can our favorite Candarian demons only manage to possess his

hand, when they have no problem possessing every inch of Linda, not just her

wounded ankle? The prototypical Final Girl is sanctified by moxie, androgyny,

and virginity. Ash gains the former, I have my doubts about the latter, but

he’s got the middle one covered, at least in name. Ash is short for Ashley.

4. Evil Dead is

a technical marvel.

Holy shit,

guys, nobody warned me that this cheap little nasty was gonna look so good.

In Donnie Darko, one of my top-five

favorite films, Donnie and his girlfriend Gertrude go to see Evil Dead. We see a few glimpses of the

film, including a shot where the porch swing pounds against the door of the

cabin as the characters approach the unlucky abode for the very first time. The

angle of the camera fucks with proportions such that the porch swing no longer

looks like a porch swing, but a misshapen Trojan Horse forcing its way through

some kind of barricade. The camera shifts as the kids approach, and the porch

swing revealed as just that, but in Donnie

Darko we don’t see that part. For years, I had no idea what the fuck that

shot was.

Does this look like a porch swing to you?

That’s the

magic of Evil Dead’s ridiculously

advanced cinematography and sound design. This film was shot by a 20-year-old

kid who spent his spare time on set poking Bruce Campbell’s wound with a stick.

He had no right to be so adept at his craft. And yet here it is, a combination

of sound and vision that transforms ordinary porch swings and trees into

indications of sheer evil unlike any horror movie before or since.

For a palate

cleanser, may I recommend the musical?

Comments

Post a Comment